Remarks from Musicians,

Dealers and Luthiers

Dealer/Luthier

Writing this article reminds me that it is over twenty years since my first meeting with representatives of the Foundation, when the aims of the organisation were outlined to me; since that time the Foundation has acquired a fascinating collection of instruments. Some of them are old friends from long back, others heard of but never seen by me before, out of reach perhaps, in foreign lands; antiques they may be, but also unique in being 'tools of trade': so they travel wherever a player is needed.

If we go back 150 years in time, when some Stradivaris were already two hundred years old, all the major instruments would be found in France or England. The two countries had the wealth and interest in music that allowed violinmaking and particularly dealing to flourish, and all the knowledge and instruments were to be found in Paris and London. The market in the USA was still in its infancy, China and Japan were closed communities to the rest of the world, but with the turn of the century, it all began to change. I understand that Western Music was first introduced to Japan during the Meiji Era (1868-1912). It is surprising to think that then the fastest means of travel was a train hauled by a steam locomotive, cars scarcely existed other than as a sort of 'horseless carriage' and flight was still some years off, but by 1914 that had been conquered. Europe spent its wealth on conflict, and the 1920's saw an accelerating trend for the musical instruments to travel west, and by the end of the 1930's they were taking to the skies as well. The world had become a smaller place, demand for the best instruments was rising; Mussolini, the Italian dictator was trying to buy the 1690 'Tuscan' Stradivari from W. E. Hill & Sons, but it all went wrong again in 1939 and Europe bankrupted itself in vicious conflict once more. After 1945, the trend for exports from Europe to the USA intensified, and more and more instruments emigrated to wealthier climes; there was no real money left in England and elsewhere to keep them, and gradually all the patrimony became depleted.

During the period of 1850 to 1950, the inheritance of fine violins and other instruments, had been carefully nurtured, largely as a result of discerning collectors and responsible makers and dealers; in the Hill firm, I can think of many examples of my seniors saying that 'so-and-so' should not be shown that fiddle, 'he will only wreck it'. What they were foreseeing, was that insensitive hands would mistreat something superb that had come through the previous three centuries virtually unscathed; all the training and tradition was aimed at preserving the instruments above all else. Never was the expression 'if it isn't broken, do not fix it' more apt, coupled with the constant reminder that we are all only temporary custodians, and therefore there is a duty of care that falls on all of us. Sad to say, there have been recent instances where thicknesses of the top or bottom plates have been reduced, because some idiot thinks he knows better than Stradivari or Guarneri, examples of whose instruments have indeed been vandalised, for that is what it is. Unfortunately, accidents do occur, which is another matter, and in much the same way that we seek expert advice from a specialist if we need complicated dental treatment, or have suffered a broken limb, so it is with any violin restoration work; you try and see the top person for whatever is needed. The very best instruments must have experienced hands to look after them, and this is one of the subjects that occupies much time in the International Society of Master Violin and Bowmakers; to try and encourage suitable youngsters with the necessary ability to develop their expertise.

The years from 1945 onwards have seen an increasing interest in music, shared throughout the world; increasing prosperity in countries that had no previous instrument market, has led to increasing demand; sadly inevitable that the greater the demand, the greater becomes the pressure on prices; not very encouraging for an aspiring student with their career in front of them.

People often ask what is involved in looking after such valuable art objects, and the answer is common-sense, really; never put away an instrument in its case before it has had the rosin dust lightly removed, do not handle it other than by the neck, do not allow any fluids such as perspiration to get on the varnish. It is also a good plan to show it to an experienced maker who will see if there is anything likely to need attention in the near future, such as correcting wear on the ebony finger-board. Sometimes the pressure on young artists leads them to take short cuts with the proper care of their instruments, which brings us back to the beginning of this article.

What was impressive to me when first hearing of the Foundation's aims, was the generosity of buying and lending out superior instruments to younger players to help with their career development, but at the same time, insisting that the instruments had to be properly looked after and cherished; and it was the preservation element that made me realise what had been missing before. This has required a truly immense effort in time and money on the part of the Foundation, for which we and the instruments should be profoundly grateful.

Some of the highlights over the last twenty years have been the ex Heifetz 'Dolphin' of 1714, which is one of the most outstanding Stradivaris, and the 1730, ex Feuermann violin cello. When acquired, it was understood that it would have to come to pieces to correct some slight deformation in the rib at the bottom edge, and the inside of the instrument was a revelation. A well-preserved example outside, the inside was virtually as it had left its maker nearly three centuries earlier, even down to the original neck block with its original nails put in by Stradivari; a tribute to the care taken of it for all those years before.

The 'Lady Blunt' of 1721, is an extraordinary violin in much the same condition as when it left its maker's hands, and it can be placed alongside the 'Messie' of 1716, that is in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, England. My family donated the 'Messie' to the museum, as we realized that it was the only Stradivari left in 'as new' state, and we felt it should be preserved as a yardstick for future makers to learn from. Acquired by the Foundation in 2008, whose intentions for preservation are well-known, none of us could have foreseen the dreadful events of March 2011; but with relief funds desperately needed, the Foundation made a most generous offer, and the 'Lady Blunt' was put up for auction in June 2011. A world record sum was realized, and the full proceeds were donated to The Nippon Foundation's Northeastern Japan Earthquake and Tsunami Relief Fund to support their efforts. I have a personal connection with the 'Lady Blunt' in as much as it was first seen by me soon after I joined the family firm, when it was sold to the USA; little did I expect that I could handle its sale a further four times over the next fifty years.

The circumstances of the last sale are a poignant reminder that we are all mortal, and just temporary custodians of the history that is handed down to us from the past; let us hope it continues to pass through appreciative hands as it has done over three centuries.

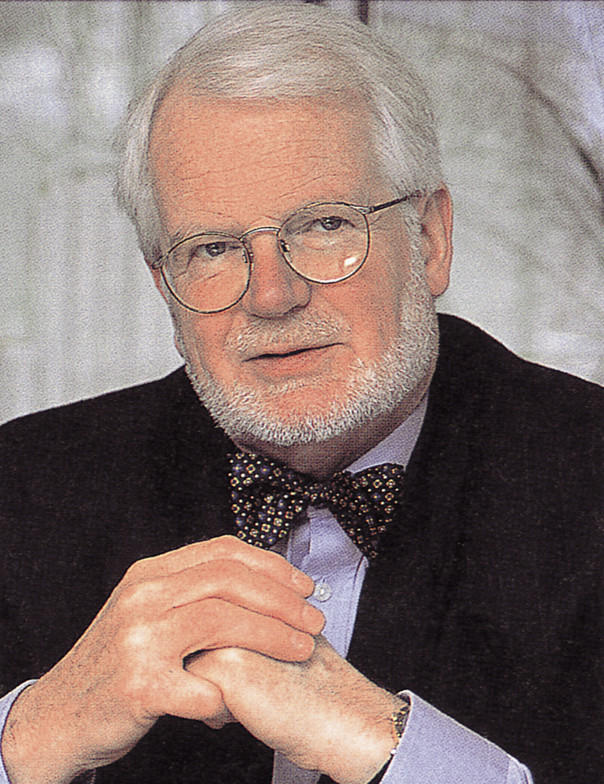

[PROFILE]

The Hill family has been in the instrument business for nearly 400 years. Mr. Andrew Hill, Nippon Music Foundation's instrument advisor, has, as he himself has said, had a slightly unusual career so far; he has served as the President of the British Antique Dealers' Association, as the President of the International Confederation of Negotiators in Works of Art (CINOA) and also as the President of the International Society of Master Violin and Bow Makers.

He started as an apprentice at the bench in the Hill firm nearly sixty years ago, spending a year in the Paris workshop of Etienne Vatelot in 1960.